Today’s date marks ninety years since the launch of Penguin Books, the world’s largest book-publishing company. Many of the world’s most beloved pieces of literature are printed with the iconic logo, which was originally sketched by its designer during a visit to London Zoo.

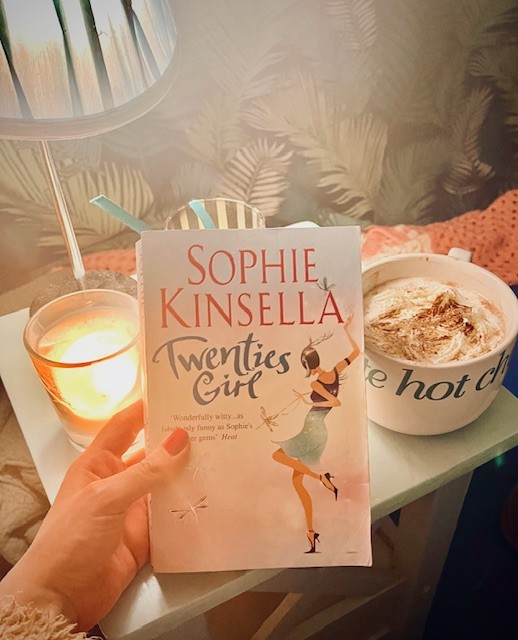

In 1934, Allen Lane (1902-1965), was inspired to set up his own book-publishing company while waiting for a train to London from Exeter St. David’s Station, as he couldn’t find anything in the station’s shop that he wanted to read for his journey. In the early twentieth century, the book industry consisted either of expensive hardback editions that could only be afforded by the privileged few, or cheap, ‘pulp fiction’ books. Lane saw a gap in the market to sell well-written books for affordable prices that could provide well-need escapism for working-class people. Britain during this time was in dire economic decline, with employment at an all-time high. Thousands of families were plunged into poverty as the economy was crippled after the 1929 global Wall Street Crash. On the 30th of July 1935, a year after his train journey, Lane and his two brothers launched Penguin Books with the aim to provide “quality books at a reasonable price” (1). The original Penguin paperbacks were sold for a sixpence each at Woolworths department stores. This would be approximately 2.5p in today’s money and would be the same price as a packet of cigarettes in 1935. These first-edition Penguin paperbacks were colour-coordinated by genre; for example, general fiction books were orange, and biographies were in dark blue. The first one million paperbacks were sold within four months of the launch (2).

Not only could Penguin’s success be measured by its impressive sales, but also by how it quickly cemented itself as one of the most influential brands in modern popular culture. Many working-class people had access to high-quality literature for the first time, and many of these novels expressed left-wing political ideas that were not typically shared in mainstream print media. Penguin is often credited with playing a part in Labour’s victory in the 1945 General Election. A 1951 article in the Daily Herald commented that Allen Lane was more influential than literary figures such as George Bernard Shaw and H.G Wells, and even Prime Minister Winston Churchill in regard to “the tastes, the thoughts, and perhaps even the character of the English” (3).

Penguin found itself involved in a legal battle in 1960 when it planned to publish the uncensored version of D.H Lawrence’s novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Telling the story of an aristocratic woman’s extra-marital affair with her gatekeeper, the novel was banned in countries across the world for its use of profanities and sexually explicit content when it was originally published in 1928. Upon hearing about Penguin’s plans, the Director of Public Prosecutions declared the book to be a violation of the 1959 Obscene Publications Act and took Penguin to a criminal court. The trial lasted six days and involved various literary and religious figures, such as novelist E.M Forster and the Bishop of Woolwich, testifying to defend the book before the jury reached a unanimous ‘not guilty’ verdict. The trial demonstrated how out of touch the British establishment was with postwar society’s ideas around class and sexuality. This was particularly highlighted by prosecutor Mervyn Griffith-Jones, who asked the jury whether Lady Chatterley’s Lover was a book that “you would even wish your wife or your servants to read” (4). Penguin’s victory in the trial is now considered to be a pivotal moment in the 1960s sexual revolution that shaped the modern, more liberal Western civilization.

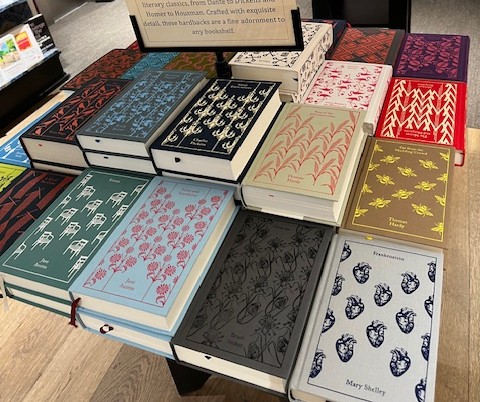

In the twenty-first century, Penguin has continued to adapt to social changes to ensure that their books remain relevant to modern readers. The invention of the internet and subsequent developments in digital technology has broadened the variety of ways in which we can consume literature. Readers today can now access Penguin titles through alternative mediums such as audiobooks and eBooks. Penguin Books now consists of eleven separate publishing houses, each creatively and editorially independent, that publish over 1500 titles per year (5). In September 2020, months after ‘Black Lives Matter’ activists around the world held protests against systemic racism, Penguin launched the ‘Lit in Colour’ scheme. This was a collaboration with the Runnymede Trust, and involved providing British schools with resources to encourage them to include more books by writers of colour in the curriculum (6).

In the ninety years since the first sixpence paperback with a funny little bird on its spine was printed, society has changed in ways that somebody living in 1935 wouldn’t have been able to fathom. Penguin is now a globally recognised brand that has made sure that literature appeals to everyone, regardless of age, gender or ethnicity. If Allen Lane embarked upon the same rail journey in 2025, his train would most likely be cancelled. He would probably be irritated by the fellow passengers in the carriage playing Tik Toks on full volume from their smartphones and who knows what he would make of the M&S premixed cocktail tins. However, it is safe to say he would be a lot happier with the choice of reading material offered to him and fellow passengers.

Bibliography

1) Penguin (a), 2025, About us (Penguin.co.uk)

2) Kells, 2015), The Penguin Books story laid bare (even the naked board meetings), The Guardian

3) JOICEY, 1993, A Paperback Guide to Progress, Twentieth Century British History, volume 4, pp.25–56

3) BBC History Magazine, The trial of Lady Chatterley’s Lover: how the ‘obscene’ book caused a moral storm, www.historyextra.com

4) Penguin (b), 2025, Our publishing, Penguin.co.uk.

5) The Runnymede Trust, 2021, The Runnymede Trust | Lit In Colour: Diversity in Literature in English Schools, www.runnymedetrust.org.

Images

Leave a comment